- Our analysis reveals the most advanced centres for life sciences in Europe, as well as the growing clout of maturing clusters like Berlin, Stockholm and Amsterdam.

- We’ve identified five distinct types of life sciences cluster across the continent, each offering investors a unique risk and reward profile.

- We’ve developed a data-led methodology to compare the strengths and weaknesses of different clusters in this dynamic sector.

Europe’s life sciences sector has continued to grow, buoyed by rising investment volumes and its successes in developing the coronavirus vaccines, among other factors. Outside of well-known centres like the UK’s Cambridge and Oxford however, the sector remains relatively nascent – making it difficult for real estate investors to assess the maturity of different clusters, how their relative strengths compare, and which locations present the greatest opportunities for investment into labs and other specialist facilities.

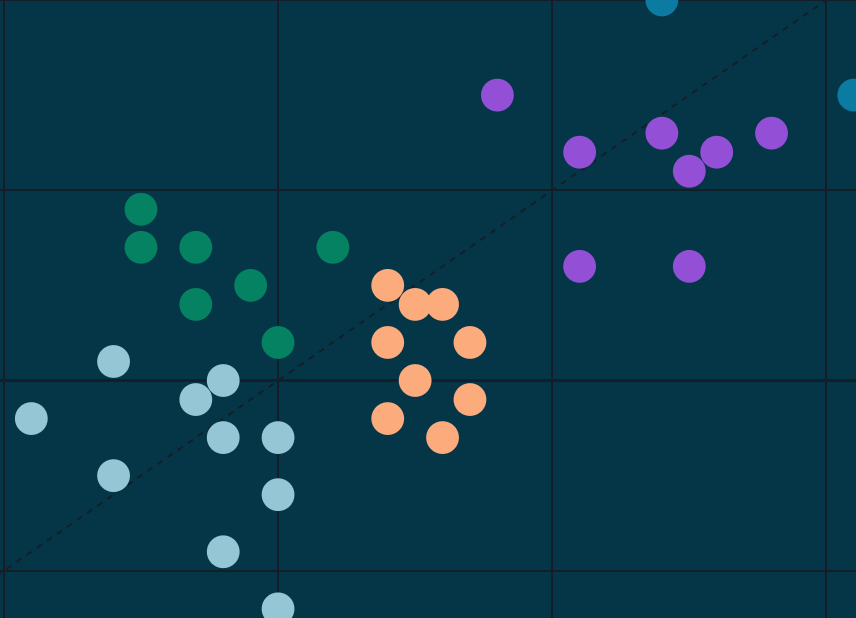

To address this, we collected and analysed market and real estate data on both the size and concentration of the local life sciences sector in 39 European clusters. We then developed a composite score for each cluster along two axes: Human Capital, which measures the depth of the local company, employment, and academic ecosystems; and Physical Capital, which summarises the level of private and public sector funding, as well as the commercial real estate offering.

After scoring each of the clusters along these axes, we placed them into one of five descriptive groups that summarises their overall performance.

This analysis provides investors with both directional guidance on the maturity of Europe’s leading life sciences centres, as well as pointing them to emerging markets that may present opportunities in the future.

How to score a cluster

To assess the maturity and comparative merits of the different clusters, we categorised the 17 variables we collected for each cluster into one of our four groups:

- Ecosystem. This includes variables related to the size and composition of the local sector, including the number of life sciences companies and the rate of startup formation.

- Talent. Life sciences employment, the number of universities and the impact of research done by these universities.

- Funding. The levels of private and public funding invested into companies in the local sector.

- Real Estate. The lab stock, the liquidity of the market for property investors, lab yields, etc.

Based on their place in the distribution of the underlying variables, each cluster was awarded a number of points that sums up to their score in the category. We then added these category scores, after some weighting, into one of our two axes: the Ecosystem and Talent scores combined to form the Human Capital score, and the Funding and Real Estate scores combined to form the Physical Capital score.

On the graph above we have plotted these composite Human and Physical Capital scores out of a maximum score of 50, which is arbitrary, but allows us to see the relative position of each cluster in relation to others.

Europe’s most established clusters – such as Cambridge, Paris and London – all score well along both axes, but the analysis also shows the strong performance of the continent’s secondary clusters, such as Berlin, Amsterdam, and Basel.

Identifying comparable clusters

To further segment the performance of the clusters, we assigned each cluster into one of five groups based on its position along the Human and Physical Capital axes. These groups are:

- European Leaders. Markets which have strong fundamentals and are dominant markets for life sciences research and development, often built on decades of growth.

- Fast Movers. Mostly composed of established markets, where strong fundamentals in either physical or human capital are positioning the cluster for fast growth.

- Maturing Hubs. Established and emerging clusters with existing solid hubs or anchors for life sciences activity.

- Cluster Specialists. Clusters that are often strong in a single fundamental, but still improving in other areas.

- Seed Markets. Less mature clusters with potential for growth, but little funding or physical infrastructure.

This segmentation provides instructive insights on the comparative maturity of different locations. For instance, many of the Cluster Specialists perform better along the Physical Capital axis than in Human Capital, as their comparative advantage lies more in the availability of funding for specialised R&D and the provision of specialised space than in significant company numbers.

Stevenage, for instance, is a specialist in cell and gene therapy, home to the GSK R&D facility, the Bioscience Catalyst, and Cell and Gene Therapy Catapult, which provide excellent infrastructure for growing early-stage cell and gene therapy companies, despite not having a local university.

By contrast, Seed Markets like Lille, Leeds, and Hamburg are arguably underserved by commercial labs space relative to their company numbers and employment levels.

The opportunity for real estate investors

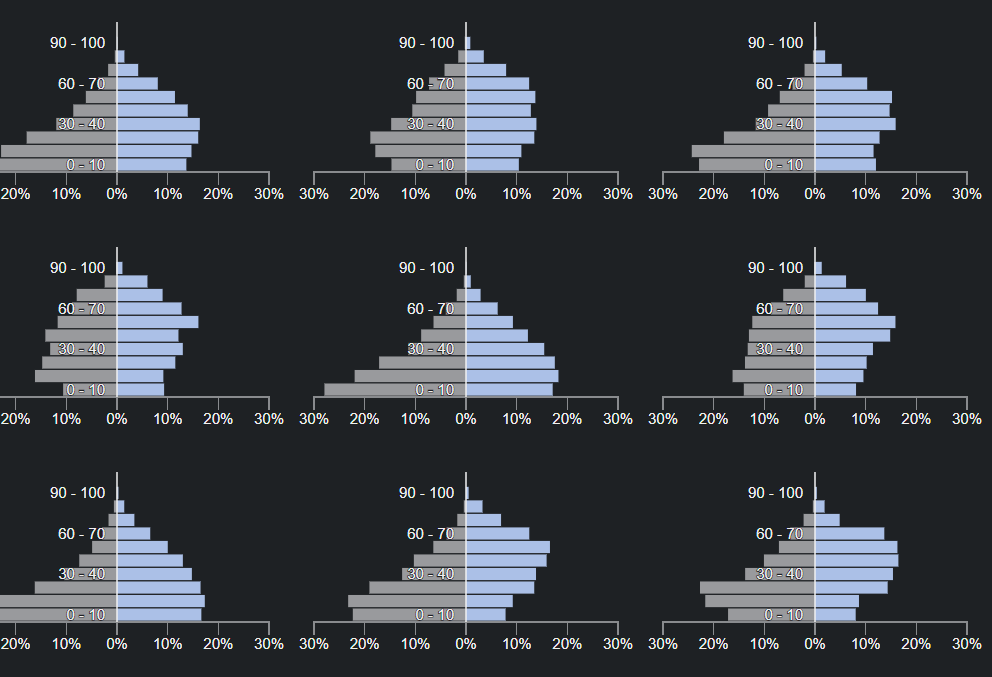

The prospects for the life sciences sector are strong. A greater consumer-reliance on medical devices, the effects of an ageing population, and rapid advancements in medical technology will drive long-term growth in the sector.

This presents considerable opportunities for real estate investors, as a growing sector will lead to greater demand for specialist stock. We envisage that Europe’s top clusters will inevitably strengthen, building on decades of growth. However, our analysis also highlights the new wave of emerging clusters, where investors who are able to deploy capital now are likely to see outsized returns as these markets mature.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Europe’s life sciences sector, download our recent EMEA Life Sciences Cluster Outlook.